Ben Bernanke came out

swinging today throwing some hard punches at those critics who say the Fed's monetary policy was too accommodative in the early-to-mid 2000s. He does so by throwing the following four-punch combination of arguments: (1) economic conditions justified the low-interest rate policy at the time; (2) a forward looking Taylor Rule actually shows the stance of monetary policy was appropriate then; (3) there is little empirical evidence linking monetary policy and the housing boom; and (4) cross country evidence indicates the global saving glut, not monetary policy was more important to the housing boom. Though Bernanke rejects the view that interest rates were too low for too long in this speech, he does acknowledge the Fed could have been more vigilant in regulatory oversight of lending standards. By far this is one of the better defenses of the Fed's low-interest rate policy of the early-to-mid 2000s that I have seen. Arnold Kling seems

convinced by this rebuttal while Mark Thoma appears more

agnostic about it. While Bernanke's case seems reasonable for the 2001-2002 period, I find his arguments far from convincing on all four points for the period 2003-2005 and here is why:

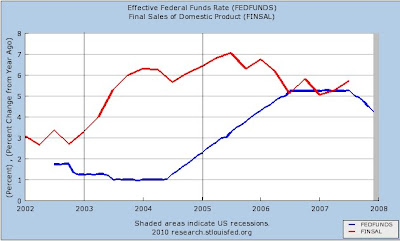

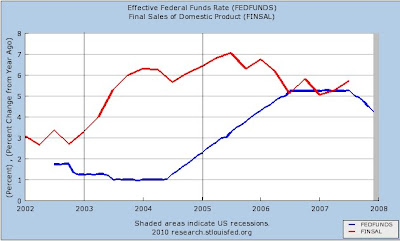

(1) By 2003 economic conditions did not justify the low-interest rate policy. Aggregate demand (AD) growth was robust, productivity growth was accelerating, and the ouput gap was near zero by mid 2003. The following figure shows the robust AD growth rate--measured by final sales of domestic product--and how the federal funds rate markedly diverged from it in 2003 and 2004 (marked off by the lines):

Note this rapid growth in AD indicates there was no threat of a deflationary collapse. Then what about the low inflation? That came from the robust productivity gains, not weak AD growth. The following figures shows the year-on-year growth rate of quarterly total factor productivity (TFP) for the United States. The

data comes John Fernald of the San Francisco Fed:

This figure shows the TFP growth rate did slow town temporarily in 2001 but resumed and even picked up its torrent pace for several years. It is also worth pointing out that this surge in productivity growth was both

widely known and expected to persist. Productivity gains, then, were the reason for the lower actual and expected inflation. [It is also worth noting that productivity growth typically means a higher real interest rate which serves to offset the downward pull of the expected inflation component on the nominal interest rate. In other words, deflationary pressures associated with rapid productivity gains do not necessarily lead to the zero lower bond problem for the policy interest rate (

Bordo and Filardo, 2004).] The big policy mistake here, then, is that the Fed saw deflationary pressures and thought weak aggregate demand when, in fact, the deflationary pressures were being driven by positive aggregate supply shocks. The output gap as measured by

Laubach and Williams also shows a near zero value in 2003 that later becomes a large positive value. As Bernanke notes, though, there was a jobless recovery up through the middle of 2003. This can, however, be traced in part to the rapid productivity gains. The rapid productivity gains created structural unemployment that took time to sort out, something low interest rates would not fix. In short, it is hard to argue economic conditions justified the low interest rate by 2003.

(2) A forward looking Taylor Rule does not close the case that the stance of monetary policy during 2003-2005 was appropriate. Bernanke cleverly constructs an "improved" Taylor rule that has a forward looking inflation component to it and finds monetary policy was actually appropriate during this time. Now a forward looking rule does make sense but invoking it now appears as an exercise in ex-post data mining to justify past policy choices. Regardless of this Taylor Rule's merits, there is still reason to believe Fed policy was too accommodative during this time. As mentioned above, productivity growth accelerated and it is a key determinant of the natural or equilibrium real interest rate. Typically, higher productivity growth means a higher equilibrium real interest rate. The Fed however, was pushing real short-term interest rates down--a sure recipe for some economic imbalance to develop. Below is a figure that highlights this development. It shows the difference between the year-on-year growth rate of labor productivity and the ex-post real federal funds rate with a black line. A large positive gap--i.e. productivity growth greatly exceeds the real interest rate--emerges during the 2003-2005 period. This gap is also seen using the difference between an estimated natural real interest rate (from Fed economists John C. Williams and Thomas Laubach) and an estimated ex-ante real federal funds rate (constructed using the inflation forecasts from the Philadelphia Fed's

Survey of Professional Forecasters):

This figure indicates the real federal funds rate was far below the neutral interest rate level during this time. These

ECB economists agree. Further evidence that Fed policy was not neutral can be found in the work of Tobias Adrian and Hyun Song Shin who

show that via the "

risk-taking" channel the Fed's low interest rate help caused the balance sheets of financial institutions to explode.

(3) There is evidence (not mentioned by Bernanke) that points to a link between the Fed's low interest rate policy and the housing boom. For starters, here is a figure from a paper that I am working on with George Selgin. It shows the gap discussed above between TFP growth and the real federal funds rate and the growth rate of housing starts 3 quarters later:

Also, below is a figure plotting he federal funds rate against the effective interest rates on adjustable rate mortgages, an important mortgage during the housing boom:

They track each other very closely. Bernanke, however, argues it was not so much the interest rates as it was the types of mortgages available that fueled the housing boom. My reply to this response is why then were these creative mortgages made so readily available in the first place? Could it be that investors were more willing to finance such exotic mortgages in part because of the "search for yield" created by the Fed's low interest policy?

(4) While there is some truth to saving glut view, the Fed itself is a monetary superpower and capable of influencing global monetary conditions and to some extent the global saving glut itself. As I have

said before on this issue:

The Fed is a global monetary hegemon. It holds the world's main reserve currency and many emerging markets are formally or informally pegged to dollar. Thus, its monetary policy is exported across the globe. This means that the other two monetary powers, the ECB and Japan, are mindful of U.S. monetary policy lest their currencies becomes too expensive relative to the dollar and all the other currencies pegged to the dollar. As as result, the Fed's monetary policy gets exported to some degree to Japan and the Euro area as well. From this perspective it is easy to understand how the Fed could have created a global liquidity glut in the early-to-mid 2000s since its policy rate was negative in real terms and below the growth rate of productivity (i.e. the fed funds rate was below the natural rate).

With that background I turn to

Guillermo Calvo who argues the build up of foreign exchange by emerging markets for self insurance purposes--a key piece to the saving glut story--only makes sense through 2002. After that it is loose U.S. monetary policy (in conjunction with lax financial regulation) that fueled the global liquidity glut and other economic imbalances that lead to the current crisis:

A starting point is that the 1997/8 Asian/Russian crises showed emerging economies the advantage of holding a large stock of international reserves to protect their domestic financial system without IMF cooperation. This self-insurance motive is supported by recent empirical research, though starting in 2002 emerging economies’ reserve accumulation appears to be triggered by other factors.2 I suspect that a prominent factor was fear of currency appreciation due to: (a) the Fed’s easy-money policy following the dot-com crisis, and (b) the sense that the self-insurance motive had run its course, which could result in a major dollar devaluation vis-à-vis emerging economies’ currencies.

Calvo's cutoff date of 2002 makes a lot sense. By 2003 U.S. domestic demand was soaring and absorbing more output than was being produced in the United States. This excess domestic demand was fueled by U.S. monetary (and fiscal) policy and was more the

cause rather than the consequence of the funding coming from Asia.

Conclusion: Bernanke fails to make a KO of Fed critics with this speech.